Howard Blackburn: onore supremo dei marinai

Nessuna storia è più drammatica di quella che Howard Blackburn combattè per la sua sopravvivenza durante una enorme tempesta a largo dei banchi di Terranova nel gennaio del 1883. Nativo della nuova Scozia, Blackburn stava pescando a largo di Gloucester con un piccolo dory ed un suo compagno;

stavano salpando le lenze per la pesca all’ippoglosso, che avrebbero stivato nella Grace L. Fears, lo schooner da cui si erano temporaneamente allontanati. All’arrivo di una improvvisa tempesta non rimase altro da fare che continuare a remare in direzione della nave. Ma la burrasca, la neve che riduceva la visibilità e il sopraggiungere della notte rendeva ardua quella che già si annunciava una impresa.

Mentre sgottava con un secchio l’acqua imbarcata a causa della tempesta, accidentalmente gettò fuoribordo i suoi guanti perdendoli. Il suo compagno non dotato del fisico possente del venticinquenne Blackburn, non resse e morì di stenti.

Rimasto solo e con le mani quasi congelate egli decise di curvarle in modo tale che potesse remare, appena in tempo prima che perdesse definitivamente la sensibiltà. Egli sapeva anche che se si fosse addormentato sarebbe morto, perciò con delle cime creò un sistema con il quale se fosse sbandato, sarebbe stato punzecchiato svegliandosi.

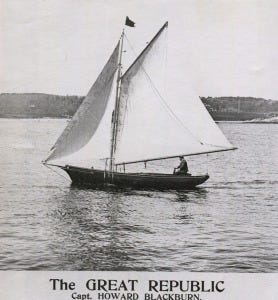

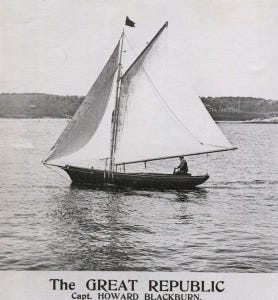

The great republic Howard Blackburn

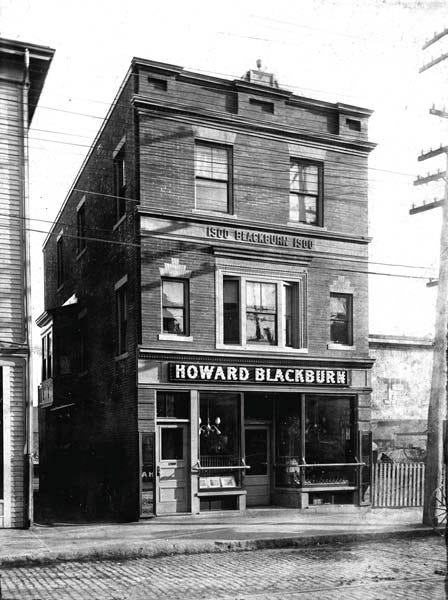

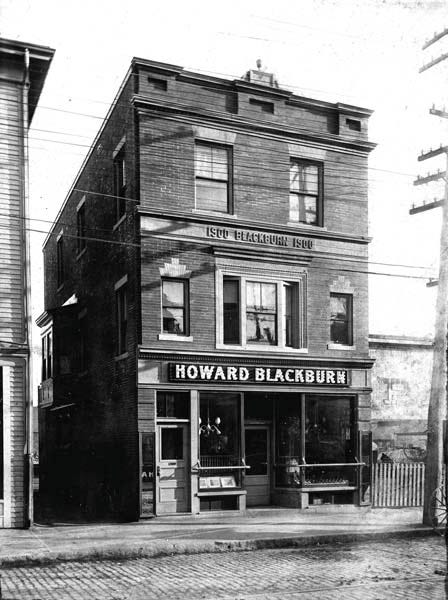

Da solo dopo 5 giorni senza mangiare tornò a Gloucester dove venne accolto come un eroe. Perse le dita delle mani, ma il suo spirito non fu intaccato. Ormai impossibilitato alla pesca, aprì un saloon di vendita di liquori con parte dei soldi (in totale 500 dollari) donatogli dalla popolazione che lo voleva aiutare a risollevarsi dalla sventura. Questa prosperità gli permise di imbarcarsi in avventure che sono divenute leggenda.

Nel 1879 si imbarcò in una spedizione per Klondike sulla scia dei cercatori d’oro, viaggio in cui doppiò Capo Horn. Nel 1899 iniziò personalmente la costruzione di uno sloop: il Great Western con cui compì in solitario la traversata atlantica da Gloucester in Inghilterra in 62 giorni. Nel 1901 con lo schooner Great Republic stabilì il nuovo record di traversata atlantica in solitario da Gloucester al Portogallo in 39 giorni.

Howard Blackburn. He was born in Port Midway, Nova Scotia, in 1858 and emigrated to Gloucester in his teens, serving as a doryman on several Grand Banks schooners. In the middle of January, 1883, he signed on board the Grace L. Fears, bound for the Burgeo Bank off the southern coast of Newfoundland beginning an adventure that would mark him for the rest of his life. In the harsh January of 1883, Howard Blackburn signed onto the schooner Grace L. Fears as a doryman, trawling for halibut from a flimsy rowboat on the Grand Banks. Ordered to retrieve the gear as the weather closed in, Blackburn and his mate, Tom Welch, were blown away from the ship in what became a five-day ordeal. On the second night, as they lay to a sea anchor, Welch froze to death. Blackburn decided to row toward land, 60 miles away. The first problem was that he had lost his mittens, and Welch’s were too small to fit him. Soon his fingers turned black, and the only way he could row was to shape his frostbitten hands into claws so that he could pull at the oars. He recalled later that when his frozen hands would strike the oar that night, “...It would sound just like so many sticks...Then the oar would strike the side of my hand and knock of a piece of flesh as big around as a fifty cent piece...The blood would just show and then seem to freeze.” Blackburn rowed for three days and two nights with the frozen body of his friend for company, beaching the dory on the Newfoundland coast on the evening of the third day. He was taken in by fishermen and nursed back to health, though he lost all his fingers and several toes. Upon his return to Gloucester, the death-defying Blackburn was given a hero’s reception, and donations of money poured into a fund set up for his recuperation. As a proper sailorman should, Blackburn used the cash to open a saloon, where he enthralled visitors with tall and true tales of his adventures at sea.

A restless nature cannot be denied, though, and Blackburn yearned for adventure. In 1897 he and some friends bought a schooner and sailed it round Cape Horn and up to Alaska, where a gold rush was under way. A year later they sailed back again, without any gold, but richer for the experience. Then Blackburn commissioned a 30ft cutter, which he intended to sail across the Atlantic to England. Great Western, as he called her, was gaff-rigged, with heavy spars and canvas sails that grew heavier when wet; how could a man with no fingers, and only the first joint of the thumb on either hand, sail such a boat, let alone accomplish all the other tasks such a voyage demands—cooking, navigation, repairs and maintenance?

The great republic Howard Blackburn The resourceful Blackburn found ways around every problem. He sailed Great Western reefed down to ease the loads, and though his crossing from Gloucester to Portishead took him 62 days, it was an accomplishment that could indeed be described as heroic. Back in Gloucester, Blackburn once again started thinking of the open sea. In 1901 he had another boat built, the 25ft Great Republic, and invited all comers to race him to Portugal. No one took him up on his offer, so he set off alone, arriving in Lisbon 39 days later after an uneventful passage. Was this enough to quench Blackburn’s thirst for adventure? No way. He had the Great Republic shipped home from Portugal, and the following year he embarked on another solo voyage, this time an inland excursion up the Hudson River to the Great Lakes, down the Mississippi and around Florida becoming in the process one of the first, if not the first, Great Loopers. Now Blackburn’s escapades began to wind down as advancing years and poor health caught up with him. He had a third boat built, this time a 17ft Swampscott Dory called America, which he planned to sail across the Atlantic to Brest, and thence down the French canals to the Mediterranean. Unfortunately, the little America proved entirely the wrong boat for such an undertaking—she capsized twice in the first few days of her Atlantic crossing, and Blackburn wisely returned to port. He did not venture out to sea again. A popular and sociable man whose saloon was always filled with fishermen and sailors, Blackburn lived out his remaining years in Gloucester, where he died in 1931.